Native Seed Library

Welcome to our Native Seed Library

We’re all about native gardening!

As a community resource, we provide you with free seeds and heaps of information for both gardening newbies and seasoned pros.

All our seeds are native to the Northeast Ohio area. From colorful native wildflowers to beneficial grasses, shrubs and trees, you can create your own pollinator habitat—whether it’s a whole garden or a single flowerpot—allowing you to enjoy the wonders of nature right outside your door.

Let’s get right to it: planting instructions

When to plant

Outdoor sowing between late fall and early spring allows seeds to germinate best…in their natural time frame. You should not plant native seeds in summer. (See “Bringing native seeds to life” below.)

Where to plant

Plant seeds on a weed-free site, clear of vegetation. Native seeds will not germinate in grass or in a weedy environment. Also, try to replicate the conditions your plant likes. Consider the amount of sun or shade; the amount of moisture it requires; the type of soil it thrives in. All are factors in a successful planting scheme.

How to sow seeds

Sow them shallowly, no deeper than the width of the seed and keep seedlings carefully weeded. Very small seeds should be surface-sown, then firmly pressed to make contact with the soil. Periodic watering is important to establish all seedlings.

First year expectations

Native plants can be slow-growing. In the first year, roots are being established in order to support top growth, so seedlings may appear smaller than expected. It takes 2 to 3 years for most native plants to mature and flower. Your patience will be rewarded!

Bringing native seeds to life

Most native seeds have built-in protections that keep them safely dormant in daunting wintry or drought conditions. In the wild, seeds will germinate only when proper (early summer) conditions prevail. In cultivation, the successful gardener needs to know that native seeds need to go through a cold period first, in order to create the right conditions that foster germination. Prairie Moon Nursery has created a set of treatments that simulate cold/wet wintry conditions. (Congratulations to those whose native seeds were sown in late fall to very early spring…their seeds have already gone through this treatment naturally.)

If you want to plant native seeds in spring, follow the germination (also called stratification) codes on the Prairie Moon Nursery website to have a good result. Prairie Moon Nursery website.

Why grow native plants

It’s a positive thing to do. Native gardening is good for the birds. Good for the pollinators. And good for us.

First, though, we must recognize the precarious position we’re in: the pollinator population is down 70% worldwide. That’s due to many things…from the overuse of pesticides to the planting of non-native plants in most all suburban yards.

After decades of planting these non-natives, our yards have become “dead zones” for pollinators. Very alarming, especially in view of the fact that we humans rely on pollinators for our own food sources!

What can we do? Let’s begin by rethinking our relationship with nature around us. We can learn about what pollinators need to survive and thrive. We can provide pollinators with the native plants that they recognize as true food sources. And we can strive to provide a friendly habitat for nature’s creatures.

Let’s all be part of the native garden movement that brings back the birds, bees, butterflies and all the other pollinators. Every garden counts. Let’s get growing…

“Everybody has a responsibility of doing things that sustain their little piece of the earth, and there are a whole bunch of things that one individual can do in that regard.” -Doug Tallamy

Best native garden practices

- Start small. Even a few pots are a sweet beginning.

- Have a garden plan in mind. There are local landscape professionals who can guide you. Some offer free services.

- Plant with a succession of flowers in mind so that pollinators will have nectar from spring through autumn.

- Provide a water source for the birds, butterflies and bees,

- In autumn, leave the leaves….rake them into your garden beds. Many butterflies and other pollinators make their winter homes in leaves.

- Also leave plant stalks and grasses up all winter. Birds need the seeds and many bees overwinter in the stems.

- Look into including host plants and keystone plants in your garden (see below).

- Work with your soil type, not against it. Check your native plant requirements for light and moisture. As the saying goes, “Right plant, right place.”

- Consider the monarchs. They depend on the milkweed family of plants.

- Avoid cultivars when shopping. A cultivar is a native plant that has been altered by humans. Many times, pollinators will not recognize these alterations and may not visit that plant. Cultivars are recognized by a name descriptor in quotes. For instance, Rudbeckia Purpurea ‘Cherry Beauty’. Any name in quotes is a giveaway. It’s best to stick to the straight species.

Learn about host plants

- Host plants are the baby nurseries of the pollinator world. Butterflies lay their eggs on specific host plants, knowing that their caterpillars will eat those leaves and eventually become butterflies.

- Some pollinators are very picky, like the monarchs. They only select milkweeds. Other butterflies are less particular.

- If you want to attract a specific pollinator into your garden, you’ll have to find its favorite host plant. Or find a host plant that is favored by a large group of pollinators.

- We have not discussed trees and shrubs, but they, too, are host plants. For instance, oak trees support an astounding 534 species, making it the mother of all host plants.

Finding the right native plant

As with all plants, native plants do best in conditions that fit their needs. Here are a few suggestions to get you started.

10 sun-loving natives (that tolerate a bit of light shade)

Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Blue false indigo (Baptisia australis)

Blazing star (Liatris spicata)

Wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

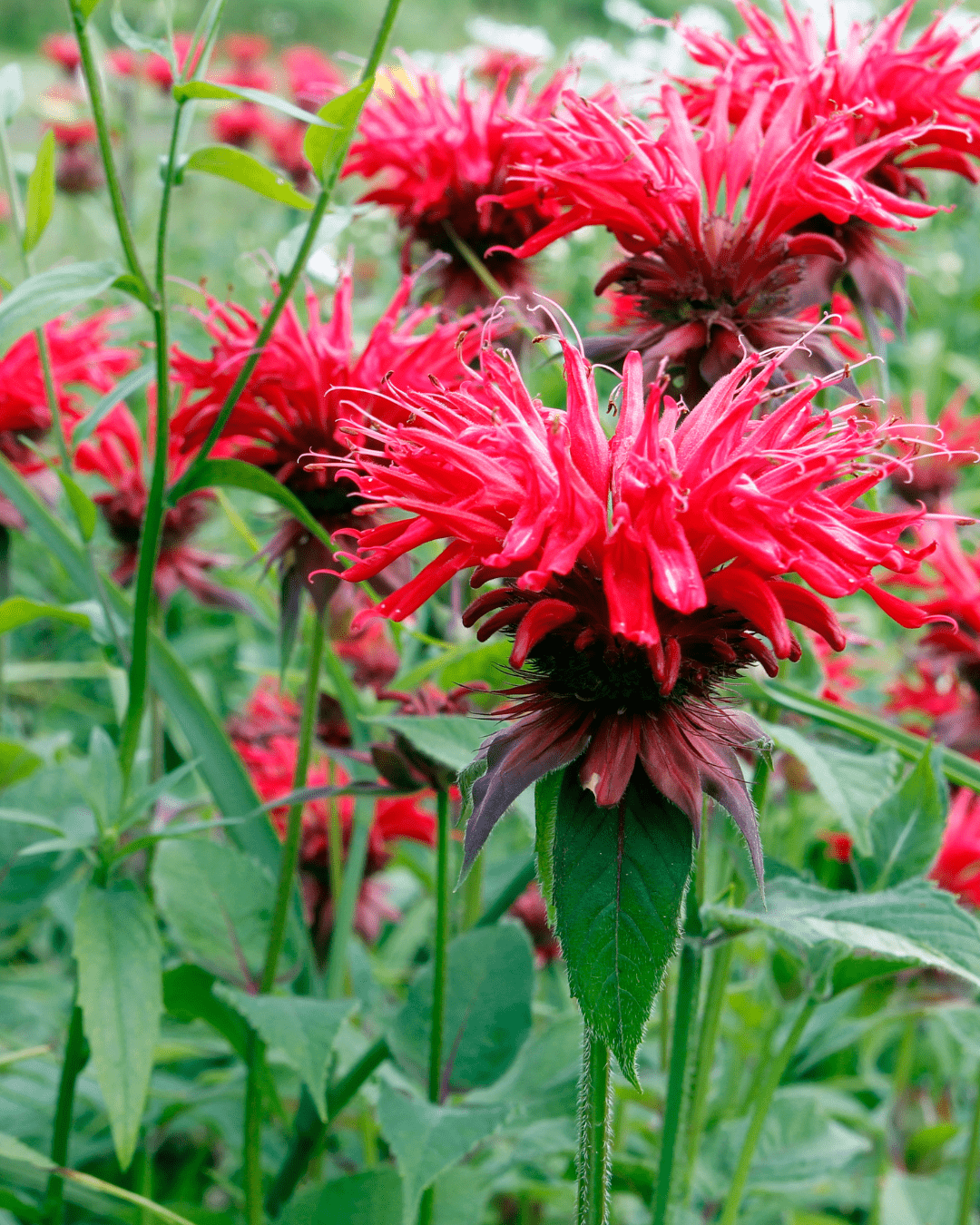

Bee balm (Monarda didyma)

Black-eyed susan (Rudbeckia species)

Blue vervain (Verbena hastata)

Goldenrod (Solidago species)

Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum)

Wild senna (Senna hebecarpa)

Shade-loving natives

Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis)

Turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

Wild geranium (Geranium maculatum)

Great blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica)

Wild ginger (Asarum canadense)

Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria)

Mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides)

Lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina)

White wood aster (Aster divaricatus)

Moisture-loving natives

Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium fistulosum, E. purpureum)

Northern blue flag (Iris versicolor)

Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis)

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum)

Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

Ohio spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis)

White turtlehead (Chelone glabra)

Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris)

Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum)

Cup plant (Silphium perfoliatum)

Clay-loving natives

Big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium)

Prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum)

Blazing star (Liatris spicata)

Stiff goldenrod (Solidago rigida)

Ironweed (Vernonia fasciculata)

Ox-eye sunflower (Heliopsis helianthoides)

Gray-headed coneflower (Ratibida pinnata)

Resources

Prairie Moon Nursery

Bringing Nature Home, Douglas W. Tallamy

Nature’s Best Hope, Douglas W. Tallamy

Garden Wildlife, Christine and Michael Lavelle

The Well-tended Perennial Garden, Tracy DiSabato Aust

Plant This Instead, Troy B. Madden

(All are available at the Shaker Heights Public Library)

The Seed Library at the Nature Center at Shaker Lakes also has new native gardening books for adults and children.

Contact a seed library volunteer for more info at ncslnativeseeds@gmail.com